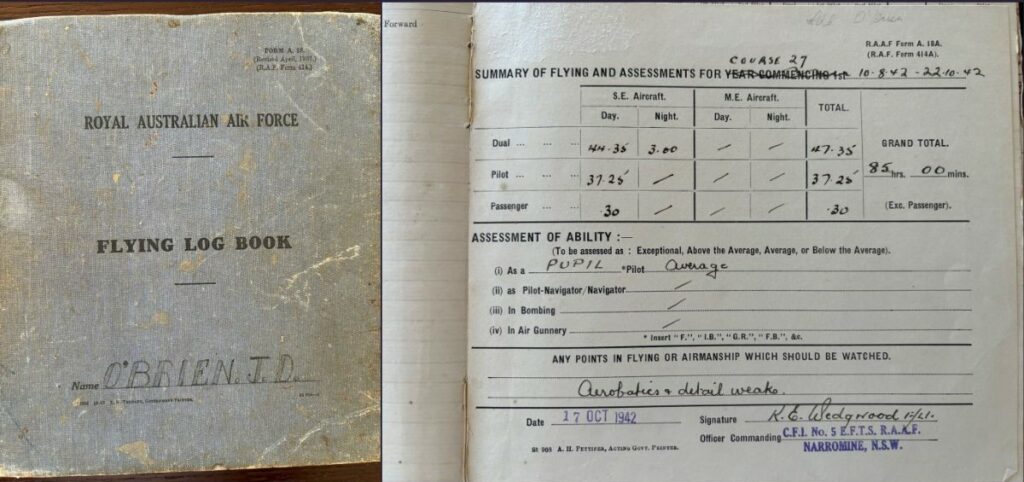

As Anzac Day rolls around each year, I inevitably find myself drawn, as if magnetically, to my Grandfather’s World War II flight logbook. Inside its blue-ish grey cover, the pages are stained by the discolouration of time, the textblock spine has separated from the leaves with the failure of the adhesive binding, while dog-eared pages speak to the points of interest of another time. Even the cursive handwriting of military men of a prior generation has smudged and run as the aniline inks succumb to the moisture exposure of 80 years of disrespect of the manuscript. But its history is seductive and each year I find some new didactic story within its degenerated pages.

This year, the lesson is that character trumps capacity and that attitude triumphs over aptitude.

Jack Dennis O’Brien was a flight lieutenant in 186 squadron with Bomber Command in England during WW2. It wasn’t the place to serve if coming home was your priority. The death rate in Bomber Command was the highest of any part of the defence forces. Tragically, 44.4% of those who served in the unit died, and a further 14.6% were either wounded in action or became prisoners of war. And those stats don’t include the more than 5000 airmen killed in training. It was treacherous work.

This year, as I poured over the ripped and dishevelled pages, it struck me that Jack was far from the poster-boy trainee. During his flight training on Lancaster Bombers between 1942 and 1944, his skills were frequently recorded to be “average” or even “below average”, and assessor’s comments observed that when it came to his airmanship, his “aerobatics and detail were weak”. It doesn’t sound like the kind of background from which a Bomber Command pilot would anticipate survival. In Bomber, a “tour” was expected to involve 30 operational sorties before a serviceman would be given his leave. Jack O’Brien flew 38 nighttime raids of Nazi Germany through enemy fire and flak and somehow managed to come home alive.

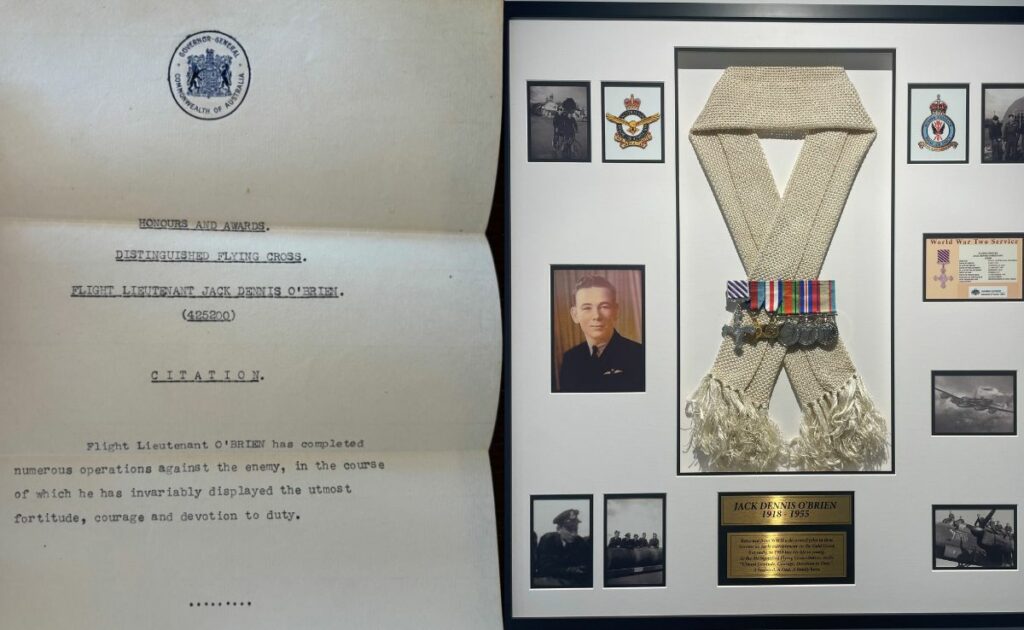

On his return, Jack was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross – one of the highest gallantry awards that WW2 airman could earn – citing his “fortitude, courage and devotion to duty”. He may not have been the most gifted student pilot that the RAAF has ever seen – far from it. But when your crew rely on you for their lives, attitude trumps aptitude and character rises above capacity. And so, to in our modern lives; perhaps you don’t need to be a genius to succeed if you have values, principles and strength of character?

This Anzac Day I’ll be reflecting on the selflessness, courage, dedication and sacrifice of all of the servicemen and women who have done their bit to protect our country and our people. To the fallen, and all who have served, we express our admiration, respect and gratitude. Lest we forget.

Managing Partner

View Bio >